The drought of London IPOs, and how virtues become roadblocks to growth.

Editor’s note: To believe that cumulative IPO volume is but another financial KPI of an economy is among the most ignorant assumptions one could make. That’s a radical statement, you may think, unusually radical for this blog, perhaps. With this article I seek to convince you that however radical it may seem; it is nonetheless true. This brief summary of the IPO market, its dynamics and key factors, combined with juxtapositions of London with other prominent IPO venues aims to substantiate a message that is felt by many, yet seems just distant enough to not make it a priority for policymakers: Europe is grossly underfinancing risk, and is thereby surrendering its global political, economic, and technological importance. Why and how that has happened, as well as real alternative courses of action are all up-in-the-air discussion topics. Do feel encouraged to share your thoughts below. Best regards, Nikita

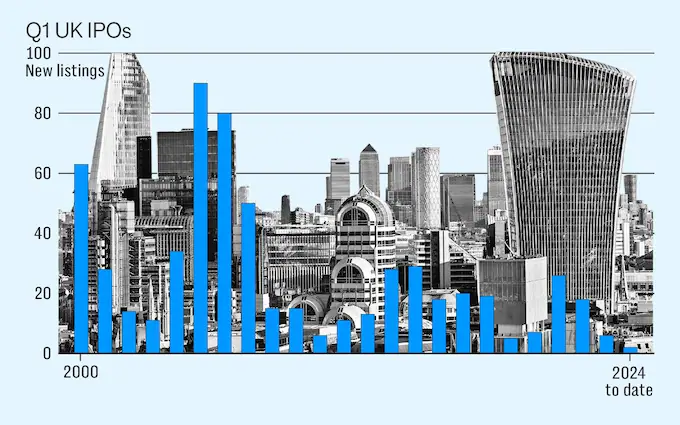

A substantial shift in dynamics across European stock exchanges following the pandemic of 2020 has, seemingly, gone entirely unnoticed. As the total value of companies listed on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) soared to $3.18tr in 2023, overtaking Paris to become Europe’s most valuable stock market, one could believe that England was successfully executing a growth strategy favorable to businesses – or at least doing so better than its continental counterparts Paris and Frankfurt. A look at IPO statistics, however, presents a far more complicated, and frankly worrying picture. Public listings on the exchange have been stagnating ever since the great financial crisis; not just in quantity but also in volume. Failing to capitalize on the global AI megatrend, the exchange’s IPO volume is on track to decline to below €1bn by the end of 2024 – a 98% decrease from its high in 2007. How is London failing its aspiring founders, and what can be copied from its more prosperous American, Middle Eastern and Asian counterparts? Let us investigate.

Good to know:

An IPO is a common occurrence for companies past their initial growth phase that are less interested in investments from equity funds and venture capital. To qualify for an IPO usually requires a company to hold an arbitrary amount of assets, exceed a certain revenue threshold, and show compliance with local legal norms and auditing standards. Each exchange is free to determine their own levels for all these benchmarks. Thus, the lack of IPOs for a particular exchange can be a result of one of two realities: Either the conditions of the exchange are unfavorable for eligible firms to consider an IPO, or simply not enough firms grow to the size required for the domestic IPO. We will disseminate both options in the order listed, in order to find out which one is most likely to be the cause.

Everything is relative - A century ago Albert Einstein taught us this maxim, and it applies to IPOs just the same as it does to physics. To understand whether the conditions of the LSE are too stringent for companies to consider an IPO, we must relativize and look outward to what the LSE’s competitors can offer and assess whether there is an incentive for firms to look elsewhere to offer their company shares.

There is an elephant in the room when it comes to comparing the London Exchange with its continental European counterparts. That elephant’s name – Brexit. As a consequence of the UK’s departure from the EU, the LSE also waved their goodbyes to a seamless access to many of Europe’s financial markets. How does this look like exactly?

First and foremost, the standardization of regulatory requirements within the EU significantly facilitated the operation of companies in European markets. Being able to use the same formats (such as the Capital Markets Union (CMU) harmonization effort) for the Portuguese and the Lithuanian branch of the same company significantly reduced costs and the bureaucratic burden. Post-Brexit, companies listing in London might face dual compliance with UK and EU regulations if they seek European investors.

The investor side of the equation has also been affected unfavorably. EU-based financial institutions could previously "passport" their services across all EU member states without needing separate regulatory approvals. This facilitated seamless access to the entire EU IPO landscape, making London an attractive choice for companies seeking a broad European reach during their IPO. The end of passporting rights following Brexit meant UK-based companies no longer benefitted from this. Instead, EU-based investors must now navigate additional regulatory hurdles to partake in investments in the UK, decreasing the resource pool available for IPOs.

When extending the frame of reference outside the European continent, the drawbacks of listing on the LSE become even more apparent. Take Saudi Arabia and the UAE as the two emerging IPO venues in the Middle East. Strong governmental support in these markets incentivizes firms to pick them as their preferred exchange. This support comes in forms of lower fees and specialized listing structures for tech and MedTech companies. As part of an effort to diversify their oil-dominated economies, these countries are using IPOs to broaden and boost other domestic industries, and Saudi Aramco’s 2019 IPO had sent seismic waves through the IPO markets cumulatively raising $29.4bn and beating prior record holder Alibaba’s 2014 offering. While the long-term maintenance of such loose IPO policy is debated by some, it is universally acknowledged to be monumentally effective, elevating Saudi Arabia into 7th, and the UAE into 5th place in the global rankings for IPO volume (per Bloomberg) – a momentous ascent, considering that ten years ago, neither were represented even in the top 20.

What markets, then, are ahead of the Middle East? Going up a step in the pecking order are Asian markets, Hong Kong, Shanghai and India, listed in ascending order. The reasons for their strength lie in their proximity to talent, as both countries have seen educational revolutions, with both nations fighting over second and third place of Unicorn founders’ nationalities ranking in 2023, trailing only behind Americans. Additionally, strong tax incentives and facilitated access to the investor base in Mainland China have solidified the Hong Kong and domestic Shanghai’s global appeal for rising stars seeking deep capital pools.

Good to know:

What is a Unicorn? A Unicorn is venture capital lingo for a startup that reaches a valuation of over $1bn. Statistically speaking, the chance of startup becoming a unicorn are within 0.00X%, with industries such as FinTech, SaaS, AI and health tech exhibiting higher likelihoods. At present, the majority of unicorns come from three regions: the U.S. (~50%), China (~20%), and India (~6%).

The Indian IPO market presents a case for itself, showcasing factors beyond the terms of the exchange helping the market to an ascent. India’s economy, growing at 6-7% annually creates a favorable environment for businesses to expand and seek public funding. Indian retail investors are increasingly active in equity markets, driven by higher financial literacy and an increasingly mature market, digital investment platforms, and a desire for better returns compared to traditional savings – all increasing the capital pool available for IPOs. Reforms to strengthen market transparency and simplify listing procedures, such as tax breaks and disinvestment programs, have encouraged more companies, including SMEs, to go public, and the growth has not gone unnoticed. The global eye has been following India’s success story - especially the eye of venture capital. VC and private equity funds are both strongly represented among Indian Unicorns and IPO candidates. India’s IPO volume has grown a staggering 160% from 2023 to 2024, and the snowball effect has resulted in a confidence boost for founders seeking IPOs. India’s soaring market reflects a confluence of strong economic fundamentals, government support, rising domestic participation, and global investor optimism. This certainly is a market to keep an eye out for.

What can be said about the U.S., and Silicon Valley in particular, that hasn’t been said yet? Its track record in birthing revolutionary companies, strong universities, and a widespread culture of entrepreneurship make the U.S. a breeding ground for startups. A strong network of daring and risk-friendly VCs dramatically increases the chances for young companies to get noticed, and their idea - funded.

The U.S. IPO market’s strength is easily discernible in the size of their funnel: Through a much higher rate of funding of startups, the absolute quantity of successes increases. Higher input increases output. The expertise accumulated through this continuous scouring for promising founders strengthens network effects, incentivizing more founders to try their luck, and awarding VCs with learning experience that they can use to more effectively steer the ships of future promising companies. In addition to the favorable funding climate, frameworks such as the “dual-class” share structures of the NYSE (New York Stock Exchange) allow founders to retain more control of their firm post-IPO, enabling them to execute long-term strategy more effectively, all supporting the U.S.'s dominance over the global exchange and IPO landscapes.

In conclusion: What can the UK learn from its international competitors? For one, the importance of governmental incentive mechanisms cannot be understated. Be it tax breaks, support programs, or other sorts of mechanisms favoring the founder, the government bears a strong responsibility for allowing SMEs to foster growth and not be increasingly punished for doing so. Structural rigidity and regulatory constraints, such as listing difficulty and the requirements to list at least 25% of company shares publicly as a consequence of the IPO, account for much of the UK market’s shrinkage.

The bureaucratic burden of the UK also shows its toll on the speed of framework adoption. Agile markets are able to capitalize on current trends by quickly enacting programs and altering conditions to profit from them. It is due to this hesitation and systemic sloth that the LSE has largely missed out on the tech and AI hype, that larger exchanges such as New York and Shanghai have been bathing in. The nature of global markets and capital mobility is that they punish sluggishness. If you cannot offer the participant what they need when they need it, they will pack up their bags and move to wherever or whomever values their desires, and their business, more. The UK must find ways to ease the burden on the LSE if it values economic growth.

The second learning comes from the erosion of the UK’s domestic institutional investment, and a Europe-wide trend of paralyzing risk-aversion. In the words of Klaus Hommels, founder of the biggest pan-European VC fund Lakestar: “Europe cannot expect growth like in the 60s and 70s without regaining the risk-tolerance it had back then. We are systematically underfinancing risk, and then wondering why our economies are stagnating.” Since the turn of the millennium, UK insurance and pension funds have increasingly been favoring more secure government bonds over equities, with domestic institutional investors holding only 4.2% of UK-listed shares – down from 45.7% in 1997 – thereby depriving the LSE of the capital base needed to prosper. This sentiment has resonated with founders, with many of them preferring the New York exchange for its deeper pockets and higher valuations. This reality is much more difficult to change, as it pertains to culture as opposed to legislation or market modalities.

Europe is in desperate need of a cultural shift from structural conservatism to one of - at least partial - growth. There is value in stability, there is no denying that. But if stability is causing stagnation and a continuous relegation of the continent’s importance in the global landscape – is it really worth it?

I implore you, the reader, to deliberate this question for a while, as it not only applies to markets and economies, but also to much of our own lives. Content and stability can very quickly spiral into complacency, and it is in your best interest to prevent them from doing so. This applies to both, individuals and stock exchanges.