How does shorting actually work, and why shouldn’t you do it?

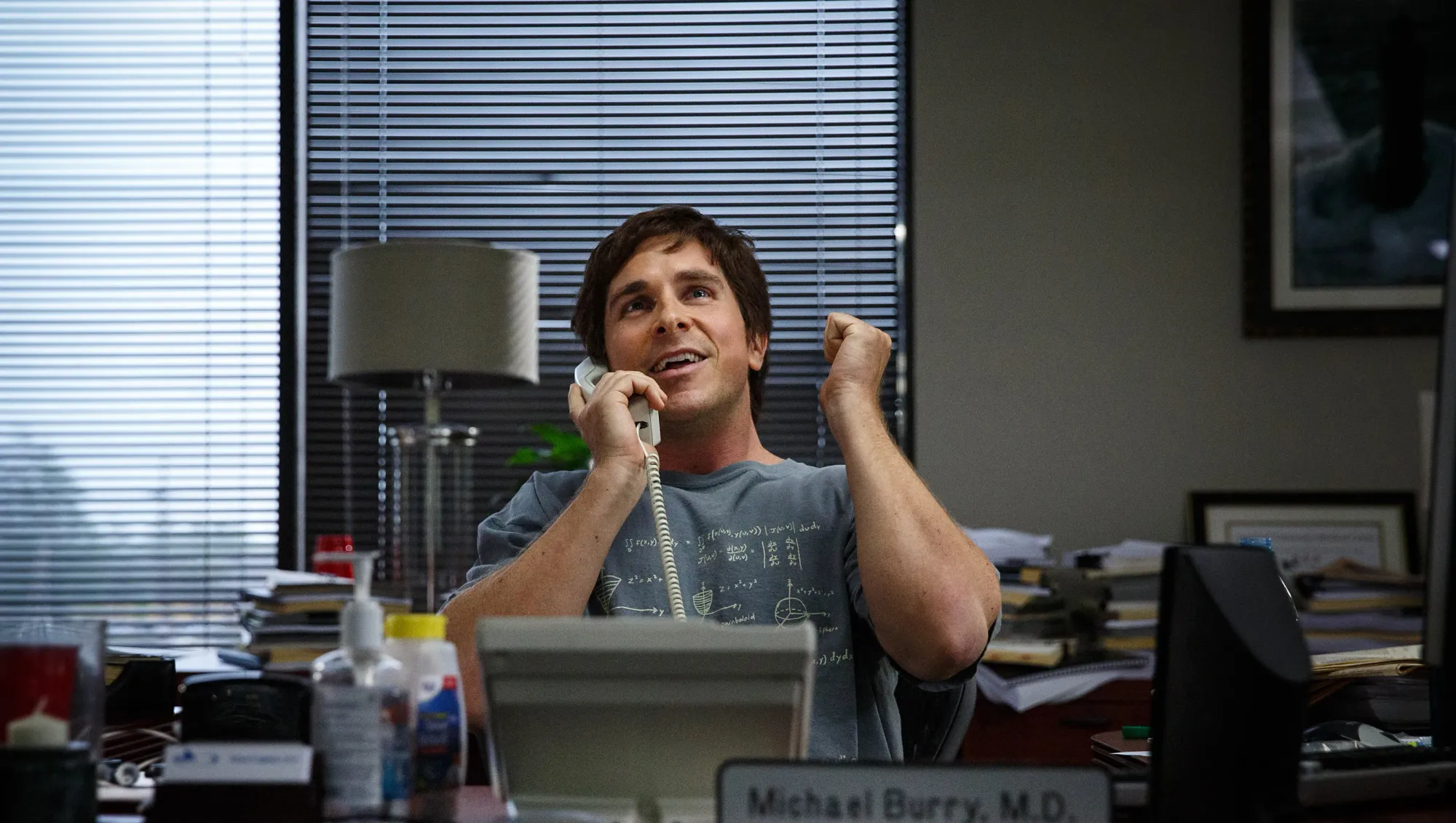

Adam McKay's 2015 "The Big Short" is certainly among the most beloved movies thematizing Wall Street and its culture. For those not in the know, the film adaptation of Michael Lewis’ book offers a glimpse into the mechanisms that led to the 2007/08 collapse of the U.S. housing market. All protagonists share one commonality: all of them bet against the Mortgage Backed Securities offered by major U.S. banks. In other words – they executed a short.

Shorting is as much counterintuitive in nature as it is opaque. In hopes of clearing the air on how one can earn money from the devaluation of a stock, I will broadly outline the mechanism of a short, and the up-and downsides thereof.

The option of shorting stocks has existed as long as the stock market itself – that is about 300 years, give or take. The simple premise of shorting is borrowing a fixed quantity of shares and selling them at a current market price, in hopes of buying them back cheaper upon the expiration of the lending period. Three aspects differentiate a short from a conventional share purchase:

- No ownership of shares

Banks and asset managers have dedicated securities borrowing departments, tasked with lending out their assets under management. It is with them that a trader enters into a contract, wherein they are obliged to return the borrowed shares on a fixed date with interest. - Terms of contract

Since it is a quantity of shares that is “borrowed”, not a sum of money, as long as the shares are returned in the same quantity, the contractual obligation is fulfilled. The delta between the current and future price is the potential profit of the short. Such a contract puts a cap on the length of the trade giving it an expiration date, upon which the bank buys the shares back at whatever the current market price is, billing the profit/loss to the trader. - Compliance and collateral

Losses are taken when the share price moves upwards. To protect the bank againt this, collateral is paid in to ensure that the trader is able to cover the buyback of the stock, should its price rise. In the U.S., collateral for short trades amounts to 50% of the trade volume. Should the stock price soar, the trader will be contacted by the bank to wire in additional collateral.

While there are advantages to shorting, namely hedging against other positions and correcting overvalued stocks, the risks are numerous. From infinite potential losses (as opposed to a “traditional” stock where its lowest price is 0), to the risk of a “short squeeze” (a rising share price forcing shorters to buy back shares to exit their positions, thereby increasing the share price further and exacerbating the cycle.) It is a strategy that requires deep market understanding and elaborate risk management. It is for these reasons that it is best left to experienced traders, and for private investors to focus on lower risk strategies.