China's deflation: a slow-motion economic crisis.

Editor’s note: After a longer break due to exams (an unexciting, perhaps, yet no less inevitable part of the student routine), it is time to formally put a start to the new year with the first write-up of 2025. This one will be short and brief and will shine a light on a topic that is much more commonly discussed than lived; that topic being deflation. In this case, it presents itself as yet another ingredient in China’s increasingly worrying cocktail of degrading economic KPIs. I will go into the theory of how deflation comes to be and do my best to try and illustrate why historically, deflation has been perhaps the most potent stimulant forcing central banks into action.

In recent years, China's economic landscape has undergone a significant transformation, shifting from the rapid growth that characterized the early 21st century to a period marked by deflationary pressures. This transition has profound implications not only for China but also for the global economy.

Deflation refers to a general decline in the price level of goods and services, often accompanied by a reduction in the supply of money and credit in the economy. Unlike inflation, where prices rise, deflation leads to decreased consumer spending as individuals anticipate further price drops, resulting in reduced business revenues, layoffs, and a slowdown in economic activity. Prolonged deflation can create a vicious cycle of declining demand and falling prices, posing significant challenges for policymakers.

To put this in more simple terms, the rational consumer understands that their dollar will buy them more goods tomorrow than it will today, as the prices of goods fall over time. The consumer therefore decides to not spend any money today, depriving the economy of private consumption – the biggest component of GDP. Less consumption means less demand, swiftly followed by production decreases further reducing economic output.

Historically, deflation has been associated with economic downturns. The Great Depression of the 1930s and Japan’s "Lost Decade" in the 1990s serve as key examples. In both cases, falling prices led to sluggish growth, mounting debt burdens, and difficulty in stimulating economic recovery. China's current deflationary phase draws parallels to Japan’s experience, raising concerns about its long-term economic trajectory.

China's journey into deflationary territory has been influenced by several factors:

1. Persistent Producer Price Deflation

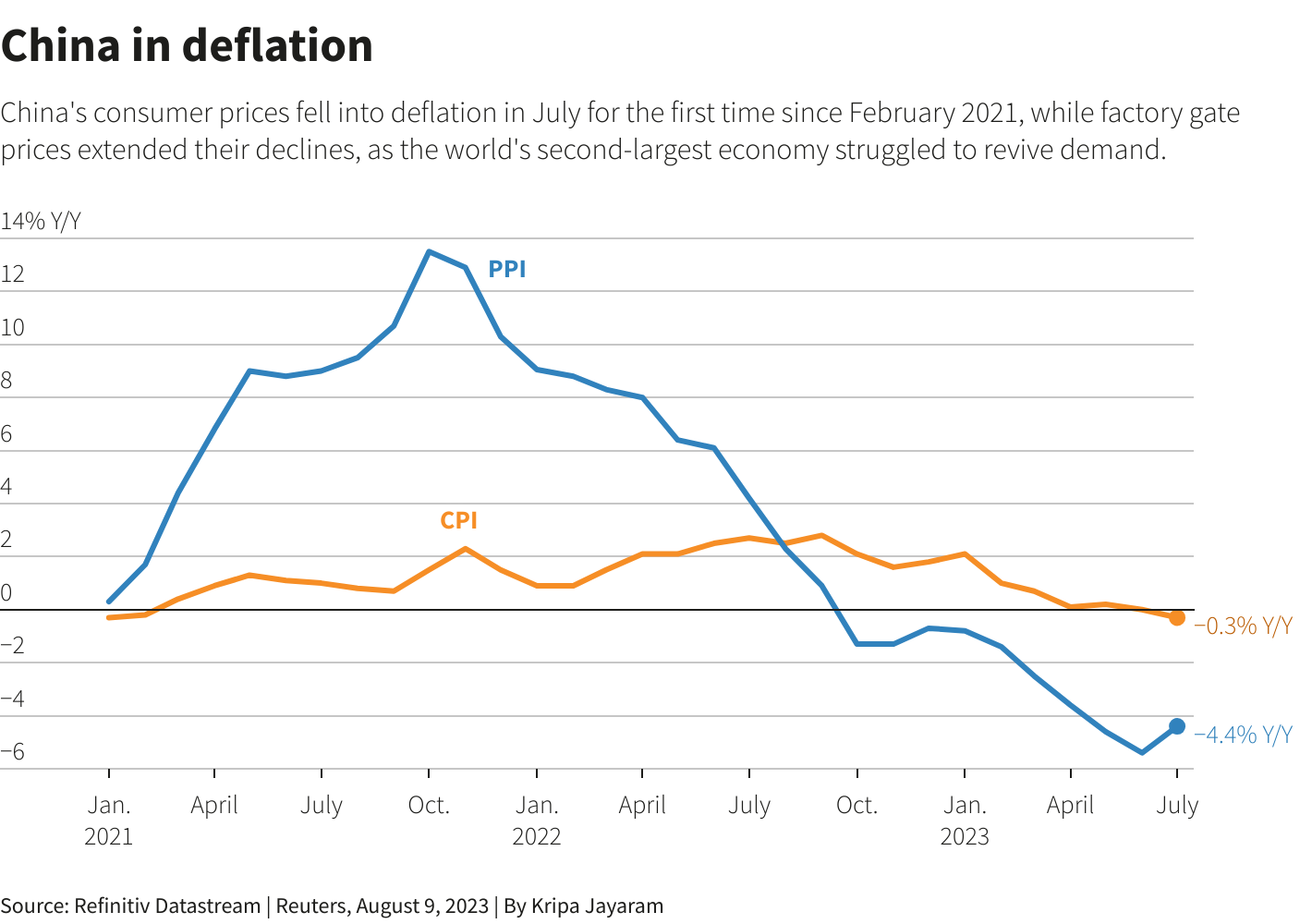

China's producer price index (PPI), which measures the cost of goods at the factory gate, declined by 2.3% year-on-year as of January 2025, marking the 28th consecutive month of deflation in the industrial sector. This persistent decline indicates ongoing challenges in the manufacturing domain, with overproduction and weakened global demand contributing to falling prices.

2. Consumer Price Inflation Dynamics

In contrast to the PPI, the consumer price index (CPI) saw a modest increase of 0.5% year-on-year in January 2025, the highest in five months. This uptick was primarily driven by seasonal factors, such as increased spending during the Lunar New Year. However, core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, remained subdued at 0.6%, reflecting underlying weaknesses in consumer demand.

3. Real Estate Market Turmoil

The Chinese property sector has faced significant challenges since 2020, with major developers like Evergrande and Country Garden experiencing financial distress. The implementation of the "three red lines" policy in 2020 aimed to curb excessive borrowing among developers but inadvertently led to a liquidity crunch, causing defaults and project delays. As of September 2023, 34 of the top 50 developers had defaulted on their debt, exacerbating the downturn in the property market.

4. Weak Domestic Demand

Despite government efforts to stimulate consumption, domestic demand has remained tepid. Factors such as high household debt, a cautious consumer mindset, and uncertainties stemming from the property market crisis have dampened spending. In August 2024, core inflation cooled to 0.3%, the weakest in over three years, highlighting the challenges in reviving consumer confidence.

5. Demographic Challenges

China's shrinking workforce and aging population contribute to deflationary pressures. With fewer young consumers entering the economy and an increasing number of retirees, the demand for goods and services weakens. The country’s birth rate hit a record low in 2023, and population decline has accelerated, echoing Japan’s demographic woes.

These ecoomic developments have not gone unnoticed. In response to mounting deflationary pressures, Chinese authorities have implemented several measures:

For the first time in 14 years, China has implemented monetary easing, shifting its monetary policy stance from "prudent" to "moderately loose" in late 2024. This change included interest rate cuts and increased government borrowing to stimulate economic activity. The move was aimed at countering the slowdown and preventing a prolonged deflationary spiral. Additionally, Beijing has introduced consumption vouchers, tax breaks for middle-income households, and subsidies for electric vehicle purchases to counter falling demand. However, these measures have yet to generate a significant shift in consumer behavior.

Fiscally, the government has increased infrastructure spending and offered incentives to boost consumption. In May 2024, the People's Bank of China announced a 300 billion yuan facility to support affordable housing, aiming to address issues in the property sector and stimulate related industries.

Recognizing the central role of the real estate sector in the economy, authorities have also taken steps to stabilize this market. Measures include easing restrictions on home purchases, providing financial support to distressed developers, and encouraging banks to extend loans to viable projects.

Perhaps hot surprinsing to anyone are the significant repercussions of China's deflationary trends for the global economy:

- Commodity Prices: As a major consumer of commodities, reduced demand from China can lead to declining global commodity prices, affecting exporters worldwide.

- Supply Chains: Deflation in China can result in lower export prices, impacting global supply chains and potentially leading to deflationary pressures in other economies.

- Financial Markets: Global investors closely monitor China's economic health. Prolonged deflation could lead to capital outflows, increased market volatility, and adjustments in investment strategies.

- Debt Dynamics: With China being a major holder of U.S. and global debt, a slowdown in its economic activity could influence interest rate policies in major economies.

With all things considered, it is evident that the future of China’s economy is up in the air. While, admittedly, economic forecasting tends to be a heavily biased and rather opaque discipline, I nonetheless would like to lay out a few possible scenarios of the country’s future, with real implications for the global markets tied in.

Scenario 1: A Prolonged Deflationary Spiral

If consumer demand remains weak and government interventions fail to stimulate growth, China could face a prolonged period of deflation similar to Japan’s "Lost Decade." This would involve sluggish GDP growth, persistent price declines, and an increase in corporate and household debt burdens.

This is without a doubt the worst case scenario for the country itself, as well as the global network of buyers and suppliers closely tied to China. The government default risk would rise, likely leading to global players pulling their manufacturing from China, as the costs with the risk premium factored in would be smaller elsewhere. While it is unlikely that the government would ever actually default, the notion of that being a possibility, and the very real accumulating debt would make foreign investors more hesitant, and leave domestic investors considering driving funds out of the country.

Scenario 2: A Stimulus-Driven Recovery

If government policies successfully boost demand, particularly in the real estate and consumer sectors, China could see a return to moderate inflation and steady growth. This would require sustained fiscal stimulus, structural reforms, and a reversal of consumer pessimism.

This, in constrast to scenario 1, is the most optimistic sequence of events. While the Peoples Bank’s economic growth target of 5% YOY would likely be out of the question (with an argument to be made that the relentless pursuit of this figure has done China more harm than good, especially in the last 5 years), growth is still very much on the table. With the global economic pie getting bigger, due to population growth and rising global wealth, China is still in a strong position to fulfil the growing demands of global markets. Industries like artificial intelligence (exemplified by the meteoric launch of DeepSeek) offer opportunities to shift away from old, manufacturing focused, economic models, to those favoring a much more mature economy.

Scenario 3: A Shift Towards Domestic-Driven Growth

As global demand slows, China may pivot toward a model that prioritizes domestic consumption and services over export-driven manufacturing. This transition would take time but could help stabilize the economy in the long run.

Much more akin to the seeming global trend towards deglobalization – at least partially attributable to the rise of populist leaders preaching self-sustenance as the hallmark of economic strength – this scenario explores the option of China abandoning much of what led them to their present fortunes. Following Marshall Goldsmith’s “What got you here won’t get you there” philosophy may prove useful for a global player with China’s dynamic and extensive financing capabilities, as the global agenda shifts and domestic market structures are reformed.

Closing thoughts:

Which scenario will actually set in, is of course a matter of guessing, though I may express my prognosis, based on my still limited understanding of the factors at play. While scenarios 1 and 2 are radical extremes, useful for visualizing the range of possible outcomes, as with most such reference points, the chance of them manifesting in their pure form is approaching zero.

As China’s economy matures, it would make economic sense to rething the growth strategy to account for the newly acquired capabilites of the country’s wealth and education system. A pivot towards the service industry, as well as a bigger focus on digitalization may be sensible to diversify the heavily industial portfolio of China’s current economy.

Ultimately, the deflation that China is experiencing is most likely attributable to the continuous belief in an ageing playbook for growth. Simply pouring in more capital and increasing the labor force only works until a critical point in the economic maturity of a country, a point that China likely reached 5-10 years ago. The present economic situation exemplifies the importance of economic pivotability and strong response-loops, as well as a fair share of humility and introspectiveness in aknowledging that the frameworks developed by prior generations do not all uphold in the modern climate. All the pessimism aside, I do truly believe that the future is bright for China’s economy, and relinquishing their global position does not seem to be on their agenda. So all that is left for us to do is watch, refine our expectations, and learn from their successes and mistakes. Will they be able to evade the fate that Japan suffered in the 90s? That is a topic for discussion.