But at what cost? China’s $380bn stimulus package, and what it means for the country’s economic future.

Editor’s note: Dear reader, I welcome you to CAPITALEIST, as this is my first write-up dedicated solely to this platform - and boy, do we have a topic for today. As with any economic forecasting, I would like to restate that we are talking about human behavior governed by factors going way beyond mathematical models - This cannot be understated. Arguments substantiated by mathematical models will be explicitly denoted, otherwise it can be assumed that the line of argumentation is based on past performance, best-practice and subjective reasoning, which may or may not coincide with future reality. Assumptions will be made, and I warmly encourage discourse about their accuracy and substantiation in the comment section. Additionally I want to stress the political neutrality of all current and future articles, as the topics are chosen solely based on their relevancy for explaining the matter at hand and are abstract from judgement and bias in spirit of knowledge and understanding.

Best regards, Nikita

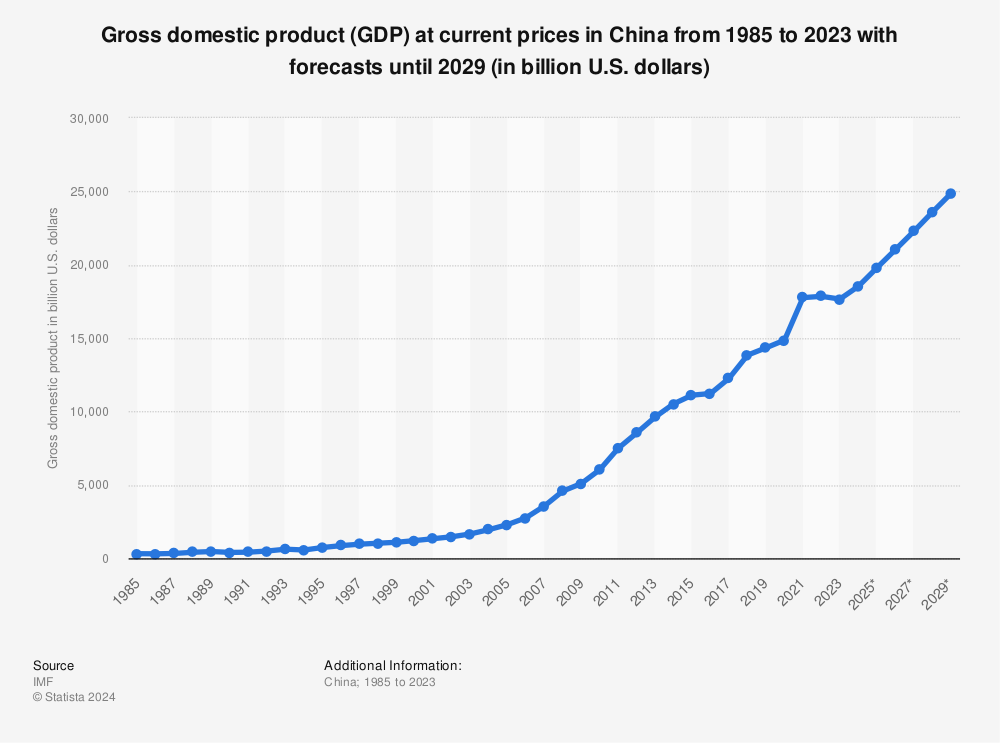

China’s economic rise has been a matter of legends. The country’s meteoric growth starting in the early 2000s under President Hu Jintao has exploded China into a global superpower, economically and beyond. It has reshaped global production, transportation, finance and real estate markets, and evoked tremble in all but the most influential global entities. Over the last twenty years China has been able to sustain constant +5% year over year (YoY) GDP growth with multi-year spurts cracking the ten percent mark. Meanwhile the world’s mightiest economy has only been able to rise above the former for 6 years in the same time span (2003-2005, 2021-2023.) Reasons are plentiful, from China joining the WTO in 2001, to heavy urbanization and large scale state-subsidized infrastructural expansion contributing to rising productivity and labor force have established China as a trade force to be reckoned with.

Worries of economic slowdown, however, started emerging at the dawn of 2024, as growth rates have slowly declined and the country’s economy seemed to forfeit the hopes of upholding the historic 5% growth mark. September 25th saw the announcement of a large scale stimulus package coordinated by governing bodies and the People’s Bank of China (China’s central bank institution, from now on referred to as PBC) in hopes of boosting liquidity in the markets. How does the stimulus mechanism work, what are its second-round effects, and what does this mean for China’s economy going forward?

What is governmental stimulus?

The textbook definition of stimulus is as follows:

“Economic stimulus refers to targeted fiscal and monetary policy intended to elicit an economic response from the private sector.” (Investopedia, 2024)

Paraphrased in regular english, stimulus in an injection of capital into select domestic industries in order to improve their market positioning or boost performance. This can be done through the (1) monetary route or the (2) fiscal route.

Monetary stimulus is an expansion of the country’s money supply usually generated through the central bank. Common instruments for this are lower interest rate cuts, lower reserve requirements for banks and the fabled quantitative easing (I will not go into the works of QE here, although I encourage you to research it on your own time, as it will allow for much better understanding of many central banks’ current behaviors.) In short, monetary stimulus aims to create an environment with more cash in it, and more incentives to spend it.

Fiscal stimulus refers to economically boosting actions enforceable by governing authorities, instead of the central bank. This type of stimulus, instead of affecting the economy as a whole, is more specifically distributed to persons, businesses or sectors. Tax cuts /-breaks as well as direct government subsidies are the most widespread practices of fiscal stimulus.

Now that the two have been formally introduced, it is important to note that their use is far from mutually exclusive. Usually (though not always), the central bank and the executive government are in agreement about the domestic economic situation, and choose to coordinate their efforts. For reasons of brevity I cannot list all second-round effects of both policy types, but it is important to understand that they often are used in conjunction to mitigate undesirable effects on e.g. inflation, currency valuation or unemployment. China’s stimulus package includes some of both stimuli types, and will be briefly outlined in the following section.

Real Estate

China’s real estate sector will see lower mortgage rates and lower down payment for second homes. Scandals such as those of the mega-developer Evergrande drowning in nearly $300bn of debt and being forced to liquidate, severely destabilized the property market and lowered buyer confidence. The measure is designed to alleviate some of the financial burden on homeowners with mortgages and incentivize potential buyers to invest more into real estate, including second homes.

Monetary Easing

Alongside the specific mortgage rate cuts mentioned in the previous section, rates are being cut across the board by the PBC. Lower interest on loans and reduced deposit rates for real estate as well as a lower Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR) seek to boost liquidity in the markets by incentivizing consumers to spend more. The RRR specifically is a metric imposing a fixed ratio of cash that banks must deposit at the central bank, as insurance against volatility and insolvency risks. These funds are inaccessible for investment use, hence a lower RRR enabling banks more access to funds for lending and investing.

Consumer Goods & Retail

Asia’s rapidly growing middle and upper class has had a tremendous impact on consumption worldwide. More specifically the luxury goods segment have experienced significant growth as a result of this, combined with the post-pandemic “revenge shopping” rally (take a look at luxury conglomerate stocks such as the giant LVMH [MCP.XC] or french luxury powerhouse Richemont [CFR.SW].) As consumer confidence drops, discretionary spending is usually the first to go. These are the costs for non-essential goods which can be easily omitted, as is much of luxury consumption. The Chinese government seeks to address this by investing more heavily into e-commerce, which has been experiencing a boom since the COVID pandemic, alongside with campaigns aiming to boost consumer confidence and reinforce the belief of a healthy economy.

While all of this may sound like China is in a dire state of a falling economy, this must not necessarily be the case. It must be noted that preceding China’s dramatic growth it was a colonized country plagued by famine and unable to keep pace with the industrialization happening in Europe and the US. Through enormous capital infusions and the rapidly growing labor force China was able to catapult itself up the ranks and achieve growth rates unimaginable for its more industrialized counterparts. This is a very typical scenario for developing countries.

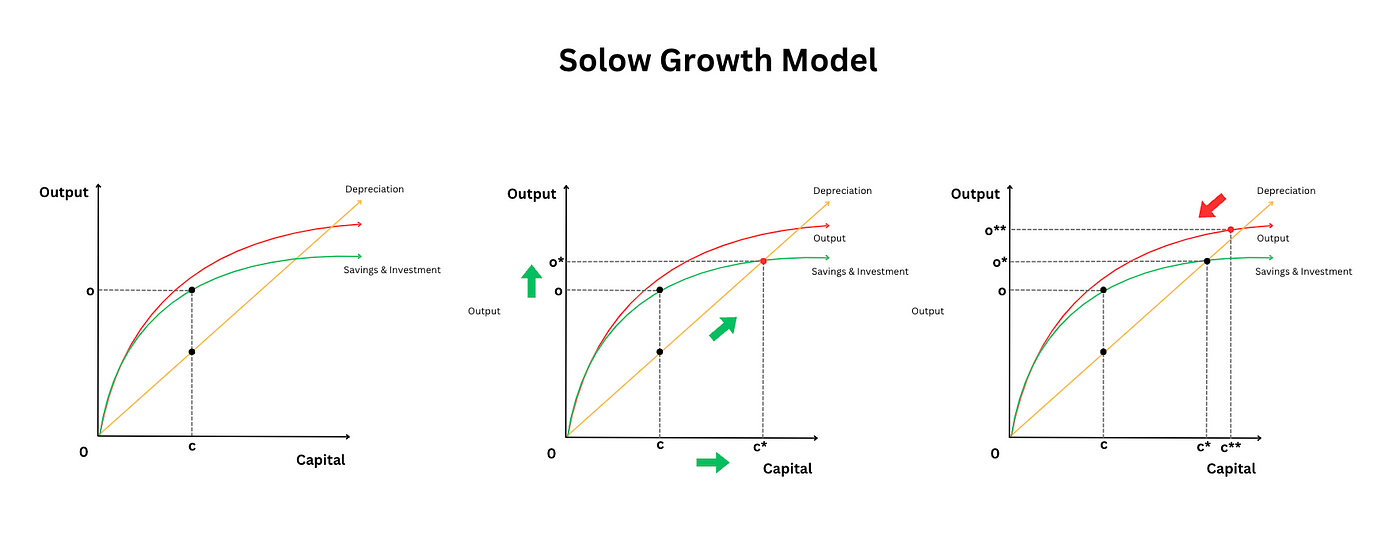

The Solow Growth Model, named after the 1987 Economic Nobel Prize winner Robert Solow, describes how capital infusions lead to exponentially diminishing output returns as the amount of capital increases. In plain English: At the beginning stages of a country’s development, relatively small capital increases lead to relatively large increases in output (GDP growth.) You can imagine this period as the time when the first factories get constructed, farmers receive better technology and the general health of the population rapidly improves due to wider access to medical facilities. Progressively, as the economy grows larger and larger, capital alone has a lesser effect - Think of the difference between 0 and 1 hospital per city versus 10 and 11 hospitals per city. A similar dynamic can be observed for labor force increases. As the diminishing returns become more apparent, the country’s path to future economic growth lies in productivity increases, which, true to their nature, are less dramatic than the initial rise from capital accumulation. It is at this point that technologies can no longer be copied from more developed countries, and resources must be invested into domestic education and R&D.

Following this logic, China’s economic slowdown is the fate of all heavily industrialized countries. Whether through denial of this reality or continuous relentlessness, the Chinese government aims to hold the sacred +5% growth rate for as long as possible. This, however, can have dire consequences, two of which I will elaborate on in the following section.

Inflation

As a consequence of large cash injections into the economy, money supply grows faster than the additional volume of goods produced. Much more available money with slightly more goods available to purchase result in a devaluation of money and overall higher prices for goods. Continuous governmental efforts to increase the pool of money in the economy have the potential to skyrocket inflation if used excessively. Periods of higher interest rates, commonly accompanied by recessions, are then due to tame the inflation rate and bring the economy back down to steady growth.

Unnatural Market Dynamics

Over-dependence on governmental subsidies may deviate markets from their natural modi operandi and result in overinflated prices, fraud and bubbles, the impact of which would be magnitudes greater than that of a more tame economic growth rate. Excessive intervention can lead to mono- and oligopolies, ultimately harming the consumer and negating the purpose of the intervention in the first place. The supply side is also affected by such practices, through distorted quantity calculations, potentially resulting in shortages or excess production.

All of that is not to say that all stimulus per se is bad; history knows countless examples of such policies achieving exactly the desired effect with great efficiency. What worries economists is the government’s seeming fixation on the 5% mark, which cannot, mathematically speaking, be held sustainably for long periods of time. It is too early to make prognoses of an overheating economy, as only time will tell. China does not have immediate issues in this regard, and likely will continue to grow for years to come, despite the momentary economic slowdown. This, however, does not negate the fact that clinging to arbitrary numbers, even when they are not feasibly (and naturally achievable is a certain path towards economic disaster.

Outlook

A viable path forward for China is relatively straight forward: keep the forward momentum that the country is experiencing now. During the course of the last 20 years the People’s Republic has gradually transitioned from adapting western technologies to developing their own, in many cases class-leading products. Industries like artificial intelligence, electric vehicles and solar panel production, among others, are strategically important sectors in which China bears unequivocal dominance. The rates of investment into education and high-tech manufacturing give no reasons to believe that this dominance will be easily forfeited to new market entrants. Assuming these factors, it may be a wise call for the economic leaders to reassess their fixation on the growth rate, as to avoid running the economy into a state of inflationary weakness, potentially resulting in losses that would severely hurt the country’s core industries.