A central banker’s new best friend, and how it scales inequality worldwide.

Editor’s note: Recessions are an inevitable part of the economic cycle - that is a fact. As much as we may not like the implications of recessions on GDP, living standards, and wages, they are a natural consequence of mankind’s ambition for more going beyond its sustainable scale. “Time is the great equalizer” is an expression known to many; “What goes up must come down” is another, and recessions are manifestations of both statements in economic terms.

Why such a sombre start, you might ask? Because it is monumentally important to establish and restate that a recession is not God’s punishment for bad behaviour - unexpected and destructive - but a natural consequence to unsustainable growth; A market correction on a national level, akin to those executed by investment bankers every single trading day. This story is about how even in times of recession our fear of stagnation and desire for more overrules our rational understanding of what is required to repair an economy running at an anaerobic pace. This is the story of QE.

Best regards, Nikita

Since the turn of the millennium the world has seen three major recessions: The dotcom bubble burst in the early 2000s, the collapse of the U.S. housing market some 6 years later, and ultimately, the one that kept all of us at home for a while, the COVID pandemic, spanning two years, starting in early 2020. All three had caused immense damage to economies worldwide, though it is the latter two that will be of particular interest to us, as a new policy type was employed by central banks to lessen the economic blow induced by these crises - A heavily criticized, yet effective policy, which also happened to fuel some of the biggest wealth-redistribution runs the world had ever seen. But let’s start from the beginning.

It's September 15th, 2008, and Lehman Brothers have just filed for bankruptcy. The world had been anticipating the crisis due to many banks, like the French BNP Paribas, freezing their mortgage-backed funds as early as Q3 of 2007, but the investment-giant’s announcement catapulted the public’s negative sentiment into outright panic. This day is widely regarded as the tipping point in the history of the period dubbed “The Great Recession”. The snowball effect of the U.S. subprime-mortgage meltdown had sent dozens of funds into a death spiral, slashed stock prices of American firms (with the S&P losing 57% (!) from its peak in October 2007 to its lowest in March 2009), and had left millions of Americans with neither a job, nor a roof over their head. The U.S. economy had experienced its hardest hit since the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the Federal Reserve was in dire need of a recovery plan. That plan was to come from then-chair of the Fed, Ben Bernanke.

The Fed had already lowered interest rates to 0.25%, though many funds rates were realistically operating even below that level. Further cuts were not an option as the Fed was facing the “zero lower bar” – interest rates so low, that lowering them further would launch the country into a deflationary spiral. The potential of using traditional monetary policy to boost the economy had been used up entirely, yet the country was still in a state of desperation – the pressure was on. That is when the Fed, with head architect Bernanke birthed the concept of Quantitative Easing into the world. It had been developed as an alternative to pre-existing monetary instruments, and as a temporary measure to rescue the economy in its weakest state. The concept was simple: economic activity was to be stimulated through the Fed printing dollars (1) and buying up marketed assets to boost their price (2), and thereby inject money into the economy (3) leading to higher output. While the concept of a central bank directly participating in the market was a novel and unusual one, the Fed saw no better alternative than to give it a shot – and it worked. Over the following years the economy slowly recovered, and by December 2012 the S&P500 had surpassed its previous 2007 peak price.

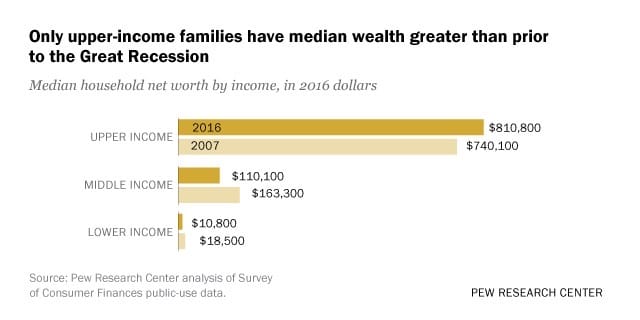

And yet, critics were getting progressively louder regarding one particularity of QE: the policy heavily favored those in possession of assets, and the more assets – the better. A small substratum of the population, mainly the economically prosperous, happened to be sitting on cash as the market price for most assets tumbled down. These individuals were able to capitalize on heavily undervalued assets, and, as the country was recovering, saw the prices for these assets rise disproportionately due to the QE stimulus coming from the government. Paraphrased in real-world terms; in times of record unemployment and financial struggle, these individuals were gaining wealth at a speed many times that of the real economy. When confronted with this Bernanke argued in his book “The Courage to Act” (2015) that QE's broader impact of stimulating economic growth and job creation was “…more important and beneficial for all Americans, particularly by improving employment levels”, than the increased inequality of wealth caused by it.

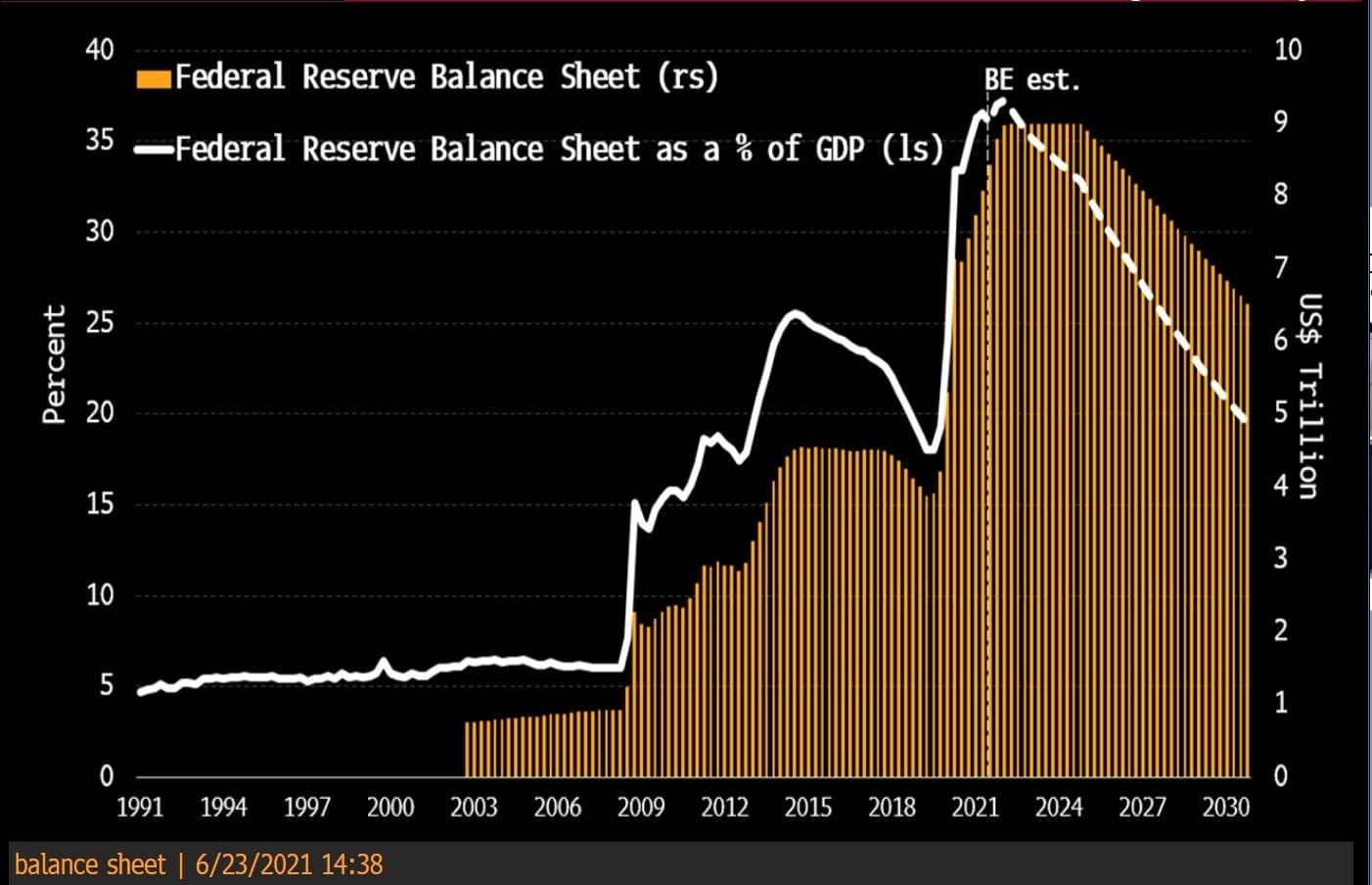

Resulting from their large-scale asset-purchasing intervention, the Fed’s balance sheet grew from $900bn in early 2007 to over $4.5tn in 2014 (a 400% / 5x increase in just 6 years) – a balance sheet that would need to be liquidated at some later date. As phase 3 of QE was coming to its end in 2014, the American central bankers transitioned to their exit strategy, considering the economy’s steady recovery, by gradually unloading the assets back into the market. America was getting back up after a shocking blow. This state would persist until the world was once again on its toes in winter of 2019, when a worrying message started spreading from the Asian continent.

Lockdown, uncertainty, loneliness, are all trademarks of the 2020/21 period following the global spread of the COVID-19 virus, and a time that many of us wish to forget. Human losses aside, the implications of a pandemic in a globalized world as we know it today have turned out to be catastrophic. Factory shutdowns, supply chain disruptions, energy crises were all met with equally novel economic measures to regain balance and control in a world that had turned from a complex intertwined mechanism into a map of individual actors, each as desperate as their neighbor. The U.S. even turned to helicopter money, a concept coined by economist Milton Friedman, by writing direct, personalized $1200 stimulus checks to boost spending and fuel the economy (it is worth noting that Friedman himself claimed helicopter money to be a purely theoretical concept, which would never realistically manifest.)

Alongside such creative measures, the now familiar QE protocols were called into action once again. Many private individuals sold off their positions at unfavorable prices, as to increase their cash reserves in case things get worse. And once again, the same story unfolded: cash-wealthy individuals bought said undervalued assets during the global market crash in spring 2020 and capitalized heavily on the meteoric rally that lasted well into the latter half of 2022, while much of the world was worried about potential job losses, financial security and their own health. In February 2019 the S&P500 lost nearly 30 percent within a month, then proceeded to double its value in less than two years’ time. The Fed hadn’t culminated their plan of unloading assets acquired in 2009-2014, yet was forced into buying more assets to boost the economy, ballooning their balance sheet to a staggering $9tn by the beginning of 2021.

To contextualize this number, at 2021 values the Fed’s balance sheet was roughly double the GDP of Germany, and roughly triple that of France. As the economy entered a correction stage in 2023, the Fed once again started selling these assets off into the markets and will continue to do so until their balance sheet is in the place Jay Powell wants it. Unless, of course, another crisis gets in the way.

Quantitative Easing has had tremendous success in combatting global recessions and bailing out countries in their weakest times. While this article may have felt like a denunciation of the principle as a whole, it is paramount to acknowledge all the successes of this still relatively novel practice. It is hard to imagine the economic state of the world, had it felt the impact of the 2008 Financial Crisis and the COVID pandemic in their full capacity. At the same time, however, as the world is increasingly plagued by inequality in wealth distribution (in real terms think of rising GDPs with falling living standards in the same economy), QE functions as an accelerator to this issue.

Marshall Goldsmith popularized the axiom: “What got you here won’t get you there”, in his eponymous 2007 book. As humans we are pattern recognition machines, hard-wired to find the most efficient solution to our problems, and to exploit it until it no longer satisfies our desired purpose. As is, it is reasonable to assume that, should there be another global economic crisis, central banks would once again call upon QE to soften the blow. Now that QE has proven itself in the markets, and its results (both positive and negative) have been quantified, Goldsmith prompts us to ask the question of whether the tool that got us here is still fit for purpose, and whether it should be the instrument of choice for future government intervention.

To answer this, we must collectively (and central bankers especially!) ask ourselves the question what our “purpose” really is. High wealth inequality causes social tensions and political instability, as well as potentially lower aggregate demand leading to lower economic growth. So:

Is a central banker’s job to minimize the immediate damage of a recession, or is it to ensure an economic climate that is favorable for a nation’s prosperity?

That is a question I implore you to answer for yourself (and maybe we can start a discussion in the comments.)

Meanwhile the best advice for private investors is to be wary of QE and the full extent of its economic impact. Alternative tools can, and undoubtedly will be developed, as QE itself is a recent invention. In times of crisis, it is a wise call to have enough liquidity on hand to allow oneself to capitalize on undervalued assets, as taking a strategic step back and forfeiting immediate returns can pay back multiples if the right opportunity is acted upon - Warren Buffet would certainly agree. (Read about Berkshire’s growing cash position here)